From RSFSR to USSR-- The Early Days of Soviet Aviation

An Introduction to Soviet Aircraft, 1917-25

By Erik Pilawskii

From RSFSR to USSR-- The Early Days of Soviet AviationAn Introduction to Soviet Aircraft, 1917-25By Erik Pilawskii |

|

It is important, firstly, to understand the current level of research pertaining to early Soviet aviation history. The military, biographical and contextual history of the early (say, 1917-25) period has recently been much improved with expanded research. Some aspects of these activities remain only partially explored, or indeed controversial (i.e. the Russian Civil War, or the campaign against the Poles), but on the whole the printed material available is certainly better than it has been hitherto.

However, with regards to the technical aspect of this history regarding aviation construction and finishing techniques and practices, virtually no significant advancement has been made since the time of VB Shavrov. We do not know now what, in fact, lacquers, dopes or other types of finish were employed on Soviet aircraft of this time. We do not (ergo) know the nomenclatures of these finishes, what their characteristics might have been, and of course-- most importantly-- how they might have appeared. All attempts to reproduce these aircraft in colour, as is done here, must be regarded as educated guesswork. We hope that this contains some considerable education; it is guesswork, nonetheless.

Furthermore, there is very considerable difficulty in understanding and interpreting photography of this period. Let us note immediately the most important point on this topic [one that is utterly relevant, by the way, to all forms of photographic analysis, from all eras]: if one does not understand the nature and technical details of the films, cameras, development procedures and other related photographic details, one cannot possibly analyze any period photograph. There are no exceptions. This point is a major failing in many attempted works based on analysis. The relevance of this reality to photography of the 1917-25 period is immense. It can be extremely difficult even to identify the type of film employed in many photos, a fact which, by itself, makes impossible any serious understanding of the image. However, even if the type of film can be determined, there is scant current evidence on development methods in use, or on the treatment of the negatives during development (manipulation of which was very commonplace). These difficulties are exacerbated by the irritating properties of many of the widely employed films of this time. Orthochromatic films, for example, being insensitive to red and yellow light, render these colours as "black" on the image, making it virtually impossible to distinguish between these three hues. Well, and the list goes on at length; the main point to bear in mind is that analysis of these images is fraught with difficulty.

With all these caveats in mind, still there is much to discover and learn about the aircraft of this period. As well, these aircraft tend to be highly individualistic, both in their finish and colouration, and also in the mechanical nature of the modifications made to them. Certainly, these facts only enhance their appeal and desirability-- they are wonderful aircraft. It is certainly high time that we study them in detail.

Part I The Nieuport 24

One of the fighter aircraft taken into the inventory of the early Soviet aviation services were Nieuport designs from France. These were the types familiar to observers of the First World War, the N.17 and N.24 predominating. Regarding the Nieuport 24, two main versions of this aircraft were see in early Soviet use, these the N.24 and the N.24bis. The 'bis' was, curiously, a bit of a retrospective design, in that the N.24's fixed fin and rudder were replaced with the older all-moving N.17 type rudder. There seem to be more 'bis' types in Russian service with Lewis gun type armament, as well, but these might also be largely examples manufactured in England (some of the Soviet N.24s were British-built machines).

The N.24bis was also manufactured in the RSFSR (that is, until 1922) in the Duks factory, later to become the famous Factory No.1 (Moscow). Production was modest, perhaps 300 or so in total, and in mid 1923 the largest number of serviceable aircraft of this type reached 125. Numbers of the N.24 in service plummeted rapidly thereafter, and it is thought that none survived past 1926.

The following are some delightful examples from early Soviet service. The photographs depicting all of these aircraft can be located in Geust and Petrov's superb volume Red Stars 4, pp. 50-55.

A Nieuport 24bis which is attributed to the 1 MIAO (Naval unit) at North Dvina,

1919 (p.54, top). The caption indicates that the unit's commander was Yakovitskij,

but no ownership of this machine is listed.

The anchor artwork certainly gives a 'navy' feel to the scheme. The aircraft looks to be finished in an over-all dull aluminum dope, possibly being similar to that used in France on the Nieuport (indeed, it may be an example imported from France). The rudder looks to be painted white, and very nicely so. The text forward of the fuselage anchor is the acronym KISA, the meaning of which I do not know. The colour of the anchor and text seems to be in agreement with the photo, in that there is a limited contrast distinction between the red stars and the (likely) black anchors.

The national markings of this period were haphazard, so say the very least. This aircraft bears red stars inside of a white disc. These appear to be very nicely executed, a feature which is exceptional rather than the norm. These stars appear in four positions, top wing uppers and bottom wing lowers.

This attractive N.24bis was said to be photographed on the Northern Front, 1919

(p.53, centre). No pilot attributation is listed.

The caption suggests red as the background colour to the skull-and-crossbones, and certainly this seems a distinct possibility. Indeed, no matter how odd it may sound, these skull markings are most likely the aircraft's national insignia! While star markings were favoured, by no means were they the uniform nor agreed national marking for Soviet forces. Some aircraft in the Civil War displayed red circles, discs, or even blobs of red paint as an identification; presumably anything red would indicate the side to which the machine belonged. In that way, one presumes this was the reason here for the red background. Curiously, also, these markings look to be present on the bottom wing lower surfaces, the rudder, and on both the upper and lower surfaces of the top wing.

The aircraft again looks to have been finished in dull aluminum dope. No other details are available.

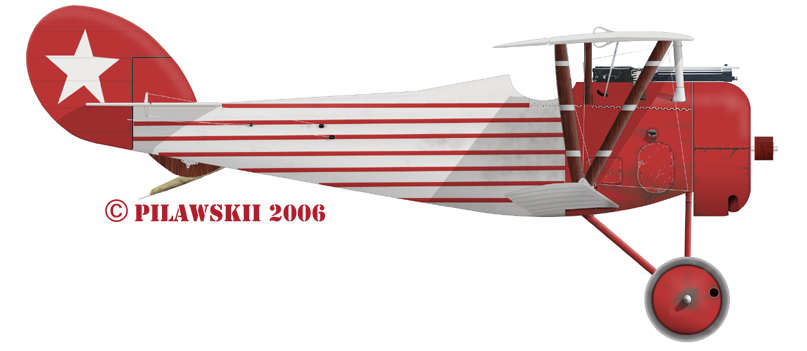

The Nieuport 24 illustrated here was said to have belonged to a special detachment

in Moscow created by cadre from the Military Flying School (p.55, right). The

date is given as 1919, but no pilot attributation is available.

The highly dramatic finish looks to be the result of applying red quite generously over the base coat of dull alum dope. Red stripes have been applied along the fuselage stringers, to the fin and rudder, the wheels, and of course to the entire nose section. A national star marking has been painted on the rudder, this obviously by hand, being quite typically oblong and asymmetrical. No other national type markings appear to be present; one presumes that none further would be needed (!).

This Nieuport 24 was photographed with pilot A.P. Shishkovskij standing in front,

certainly giving the impression (at least) that it may well be his personal

mount. No date is given, but the same pilot operated a very similarly marked

N.24bis during May 1920 (p.54, p.52).

The basic finish again looks to be over-all alum dope. National markings in the form of red stars superimposed over white discs are clearly and skillfully presented. These appear again in six positions (one might say in the WW1 'Nieuport manner')-- bottom wing unders, top wing upper and lowers. The rudder appears to sport a plain red disc, this on a white background.

No other markings or decoration can be seen. Shishkovskij's bis fighter looks virtually identical.

Nieuport 24bis s/n 4309 was photographed in a wrecked condition near Moscow,

1921 (p.53, bottom). No pilot is listed for the aircraft.

Being in such condition, the profile is certainly a reconstruction. The wing surfaces are not in view, and so sadly we cannot see if national markings are present there. The rudder carried delightful stripes in what looks to be red and white. The aircraft's serial number appears on the rear fuselage, and what might be the designation "Nieuport 24 bis" (does this suggest French manufacture, I wonder??). The most interesting feature, however, is the rather passable looking plain red star type national marking on the fuselage. This insignia would not look out of date at any time up to 1945; one wonders if examples like this one help to establish the later markings?

Alas, nothing else seems to be known about this attractive aircraft.